Let's dive deep into electronics and explore the Electro Harmonix LPB1 and Screaming bird at once !

Guitar preamps: are they a scam?

Welcome to the workshop! You may have already heard about preamp pedals, or preamplifiers, or perhaps you’ve come across the term when talking about microphones and audio interfaces. Let’s take a look together at what a preamp actually is, and more specifically, what a preamp pedal for bass or guitar really does. Because, as you’ll see, most so-called “preamp” pedals on the market are quite the scam!

1. Studio preamps

When sound engineers, audio gear manufacturers, or plugin developers talk about preamplifiers (also called preamps), they are always referring to the input circuits found in mixing consoles and audio interfaces.

These are simply electronic circuits designed to attenuate or amplify an audio signal — most often coming from a microphone, but sometimes from drum machines, external effects, synthesizers, or simply an electric guitar. These circuits usually have a variable gain, a phase inversion switch, a 48V phantom power switch for certain microphones, and sometimes EQ options or even a DI (Direct Injection) input designed for guitars or basses whose output impedance is too high for a microphone preamp to handle correctly.

In short, preamps bring a wide range of sound sources to the same electrical level and impedance, so that the signal can continue along the audio chain for processing and recording. These electronic circuits can be standalone — often in 19-inch rack format or API 500 modules — or built into other devices such as sound cards or mixing desks.

Finally, there are, in my opinion, two main types of studio preamps: those designed for transparency, and those that aim for coloration. The first type seeks maximum dynamics without distortion, minimal noise, perfect impedance matching, and the widest possible frequency response. Examples include Audient, Neve, or Focusrite preamps, as well as those built into many audio interfaces, which often have additional cost constraints that force compromises. The second type includes all the vintage or tube preamps such as the Universal Audio 610 or the Chandler preamps. These may not have the cleanest response or the lowest distortion, but they deliver a rich, intentional tone when driven into saturation.

In all cases, studio preamps are designed to handle a wide range of sources, which means they have a broad frequency response and a fairly uniform gain: the bass, mids, and highs are amplified quite evenly, with little distortion unless pushed hard. Their main purpose remains the same: to adapt the source so that it fits the rest of the audio chain.

2. Preamps in guitar amplifiers

Because the electric guitar signal is quite peculiar, almost all guitar amplifiers include a preamp stage. In addition to gain control, the preamp section of a guitar amp usually offers a simple tone control or a more complex EQ (bass/mid/treble or even a graphic EQ), allowing the musician to shape the instrument’s frequency response to get the snap, warmth, or roundness they’re after. The preamp also adapts the signal level and impedance so the power amplifier can properly drive the speaker.

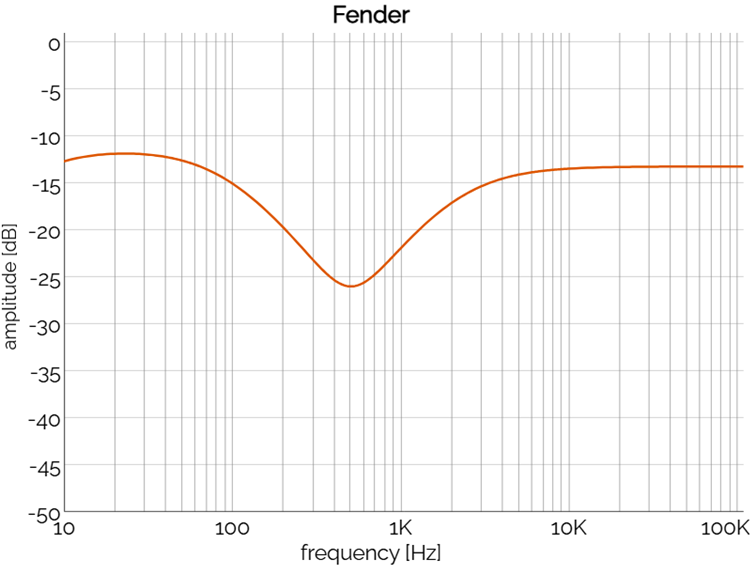

Guitar preamps are quite specific in their design. Leo Fender, a true perfectionist, understood that the coil winding of guitar pickups tends to create electrical resonance (see my article on cables). This resonance and the pickup configuration make the sound of an electric guitar naturally mid-heavy and not very dynamic. To compensate, he designed his amplifiers with tone stacks that deliberately cut the mids, which means that when bass, mids, and treble are set to noon, there is actually a real dip in the midrange!

You can play around here to see what the tone controls on your amp actually do: https://www.guitarscience.net/tsc/fender.htm#RIN=38k&R1=100k&RT=250k&RB=250k&RM=10k&RL=1M&C1=250p&C2=100n&C3=47n&RB_pot=LogA&RM_pot=Linear&RT_pot=LogA

Even more surprising: on this Fender tone stack, to get a “neutral” sound, you need to set the treble to zero, the bass just above that, and the mids all the way up — absolutely not what you’d expect!

Each manufacturer then adapted the recipe to their liking to compensate for the natural lack of lows and highs in the guitar signal: “bright” switches, presence or depth controls, graphic EQs — everyone has their own method, but the common denominator remains that typical mid-scoop of a standard tone stack. Marshall, Vox, Mesa Boogie, Soldano — all of them use this principle and apply different filters to give their amps their own voice and unique character, much like John Mayer would do by stacking multiple overdrives.

Most amps also feature an effects loop, which serves as a real point of reference: the preamp comes before the loop, and the power amp after. This makes it possible to place modulation, delay, or reverb effects in a natural position, without drowning them in amp distortion.

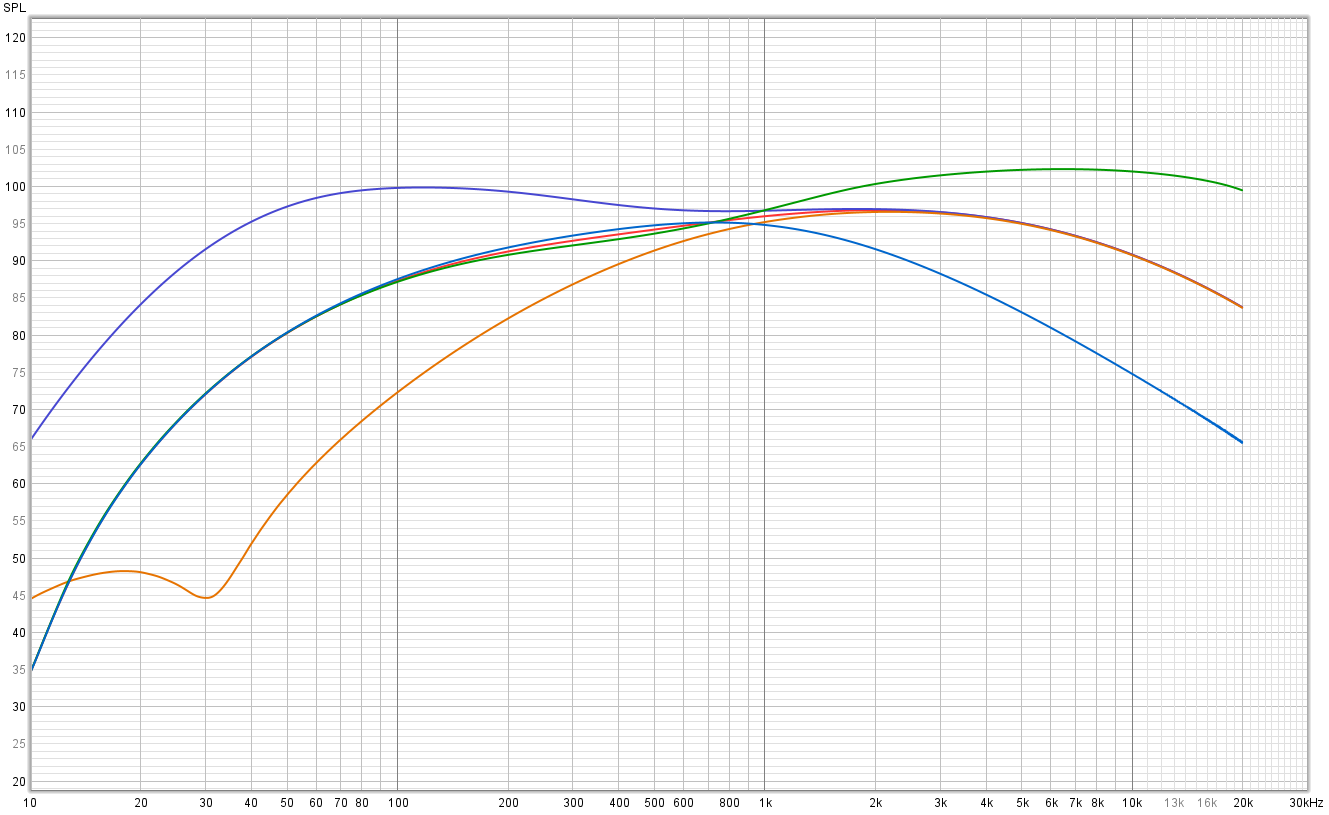

3. Preamp pedals and other overdrives

This mid-scoop, in my view, is the defining characteristic of true guitar preamps — and therefore of real preamp pedals, which are designed to be connected directly into the return of an amp’s effects loop. Examples include the Effectrode Blackbird or my own Gazelle. Both use vacuum tubes and, more importantly, display that distinctive midrange dip of a genuine guitar preamp. The second characteristic of a preamp is its typical distortion signature, which is not mid-focused like overdrive pedals, but more wideband and with many more high frequency harmonics, as an electric guitare does not produce many by itself.

By the way, the reason overdrive pedals pair so well with amplifiers and help guitars cut through the mix is that they actually bring back those missing mids in a way that makes the instrument stand out musically, without piercing the listener’s ears — try a treble booster into a Fender Deluxe Reverb and you’ll see what I mean!

So why did I call it a scam earlier? Quite simply because most “preamp” pedals for guitar are nothing more than standard overdrives or boosts, and the term “preamp” has become a trendy marketing gimmick.

Take the Xotic BB Preamp, for example. It’s basically a Tube Screamer with an active bass/treble EQ. Here’s the frequency response as the two knobs are swept from minimum to maximum:

There’s clearly no trace of that characteristic mid-scoop you’d expect from a real guitar preamp. Some overdrive pedals, however, can get close to what we’d expect from a preamp — but only if they include a midrange control, like the Singer Overdrive.

The EP Preamp, the Anasounds Tape Preamp, and other similar boost pedals also lack that signature mid-scoop, but with a good excuse: their circuits are based on the preamps found in tape echoes — that is, studio gear! We can forgive them for that, and they’re better used as boosts or EQs at the end of the chain to color the sound.

A quick note about bass preamps as well: these are much closer to what you’d find in a studio setup, since the electric bass doesn’t have as much midrange content as the electric guitar, and it’s often possible to mix the instrument directly using a simple equalizer to get a usable tone. Bass preamp pedals therefore aim primarily to shape the instrument’s EQ, and less often to add saturation or compression. However, for practical reasons, they very often include an XLR DI output, allowing the sound engineer to take the preamp’s signal directly. Generally speaking, bass players tend to be more reasonable—and they’re less frequently targeted by the flashy marketing often seen in the guitar world ?

Finally, some active guitars and basses include a true onboard preamp circuit, with volume and active EQ controls. This design is usually intended to manage the instrument’s tone as early as possible in the signal chain, providing control over the frequencies sent to the rest of the rig. In that sense, we’re back to a more “studio-oriented” definition of a preamp—conceived more as a tool than as a central tone-shaping component.

So, scam or not? More of a marketing game, as usual! It’s true that “neutral” pedals can be considered preamps in the studio sense — with a flat frequency response, similar to full-range overdrives, and bass/treble EQ controls. But in my opinion, a true guitar preamp should be designed to replace or complement the one already built into your amplifier, or even eliminate the need for an amp entirely if it includes a speaker simulation. So be cautious with fancy marketing terms and always do your research before buying: boost-style “preamps” and overdrives definitely won’t give you the same sound!

Leave a comment